Posted 23 April 2023

Associate Professor Shiang (Max) Lim and Dr Jarmon Lees have each been awarded Medical Research Future Fund Grants for their projects to deliver new treatments for the currently untreatable debilitating genetic disease, Friedreich ataxia heart disease.

Friedreich ataxia is a hereditary neuromuscular disorder that affects one in 38,000 Australians. It is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 5 and 18 and it quickly and ruthlessly robs those diagnosed of their mobility. The life expectancy of people with Friedreich ataxia is limited, with heart disease being the most common cause of premature death.

Friedreich ataxia heart disease is a complex and progressive disease with no known cure or treatment. This is something that Max, Jarmon and their teams are aiming to change.

One of the hurdles to understanding how and why heart problems occur in Friedreich ataxia is that there has been no good model of the disorder using animals or cells grown in the lab. Developing such a model has been a particular challenge because the heart is a complex organ made up of a mix of different cell types, including heart muscle and blood vessel cells, as well as nerve cells that control heart rate and rhythm.

“We develop in the womb from a stem cell. We now have ways to ‘wind the clock back’ by turning cells from an adult back into stem cells. We can then apply different conditions to coax these stem cells to form all the different cells which make up the heart,” said Max.

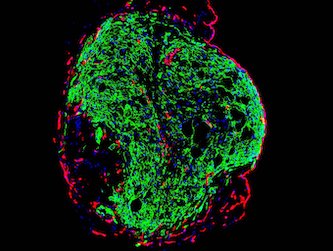

After making the different cell types, the researchers combine the cells together in a dish in the lab. After as little as a few days, the cells form an organoid that beats rhythmically. Excitingly, they can use cells that are derived from people with Friedreich ataxia, mimicking in the lab the heart of a person with the medical condition.

In two separate projects, Max and Jarmon will use these ‘hearts in a dish’ to test how they react to libraries of compounds – made up of thousands of different potential drugs.

“These ‘hearts in a dish’ allow us to test drugs that are already approved for other medical conditions and see if we can repurpose them into effective treatments for people with Friedreich ataxia,” said Jarmon.

In this way, the team ultimately aims to provide new hope to young people diagnosed with the disease.